Featured Collections

- Illustration Collection

- All Illustrations

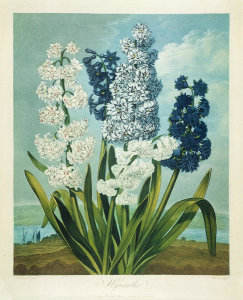

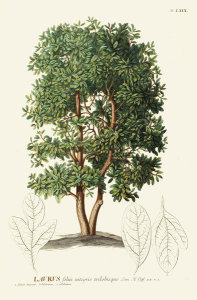

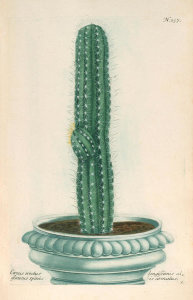

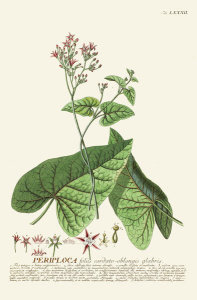

- Botanical

- Children's

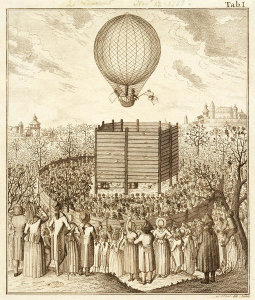

- Historical

- Natural History

- Political

- Scientific

Individually made-to-order for shipping within 10 business days.

Subjects

- Flowers and Plants

- All Flowers and Plants

- All Florals

- Exotic Plants

- Medicinal Plants

- Leaves

- Wildflowers

- Roses

- Poppies

- Carnations

- Magnolias

- Featured Subjects

- Cacti and Succulents

- Astronomy and Space

- Sea Creatures

- Activities

- Fantasy

- Magical

- Transportation

- Typography

Prints and framing handmade to order in the USA.

Artists

Your order supports The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Best Sellers

- Elisabeth M. Hallowell, California Poppy

- Edward Hopper, The Long Leg

- Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy

- Mary Cassatt, Breakfast in Bed

- Charles Francis Annesley Voysey, Snake Amongst Flowers

- Emma Homan Thayer, Yellow Poppy

- Joseph Wright of Derby, Vesuvius from Portici

- Mark Catesby, The Laurel Tree of Carolina [Magnolia Grandiflora]

- John James Audubon, Louisiana Heron

- Robert John Thornton, The Blue Egyptian Water Lily

- Charles Altamont Doyle, A Fairy Girl Reclining on a Toad Beneath a Small Shrub

- Ernst Haeckel, Trochilus

- Elisabeth M. Hallowell, Monkey Flower

- Emma Homan Thayer, Wild Peony

- Walt Kuhn, Top Man

- Kono Bairei, Bairei Picture Album of One Hundred Birds, plates 23/24

- Thomas Lawrence, Sarah Goodin Barrett Moulton: "Pinkie"

- Etienne Léopold Trouvelot, Total Eclipse of the Sun

- John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds

- Martha Benedict, Japanese Garden in Spring at the Huntington Botanical Gardens

Customize by your choice of paper or canvas, item size, and frame style.